27 September 2022 | Updated 17 October

Journalism in handcuffs

Monopoly on truth and the right not to know

Truth to power without power of truth

Western governments like to lecture other countries about the values of democracy, freedom of speech and human rights. But when the spotlight falls on human rights violations and abuse of power within those so-called democratic nations, all we get is stunning hypocrisy at best and deafening silence at worst.

Transparency, integrity, and the rule of law are expressions that Western higher officials like to toss carelessly around to maintain the illusion of their moral high ground. Luckily for us ordinary citizens, to some people speaking the truth is still a matter of conscience and acting out of principle still supersedes any form of personal comfort or interest.

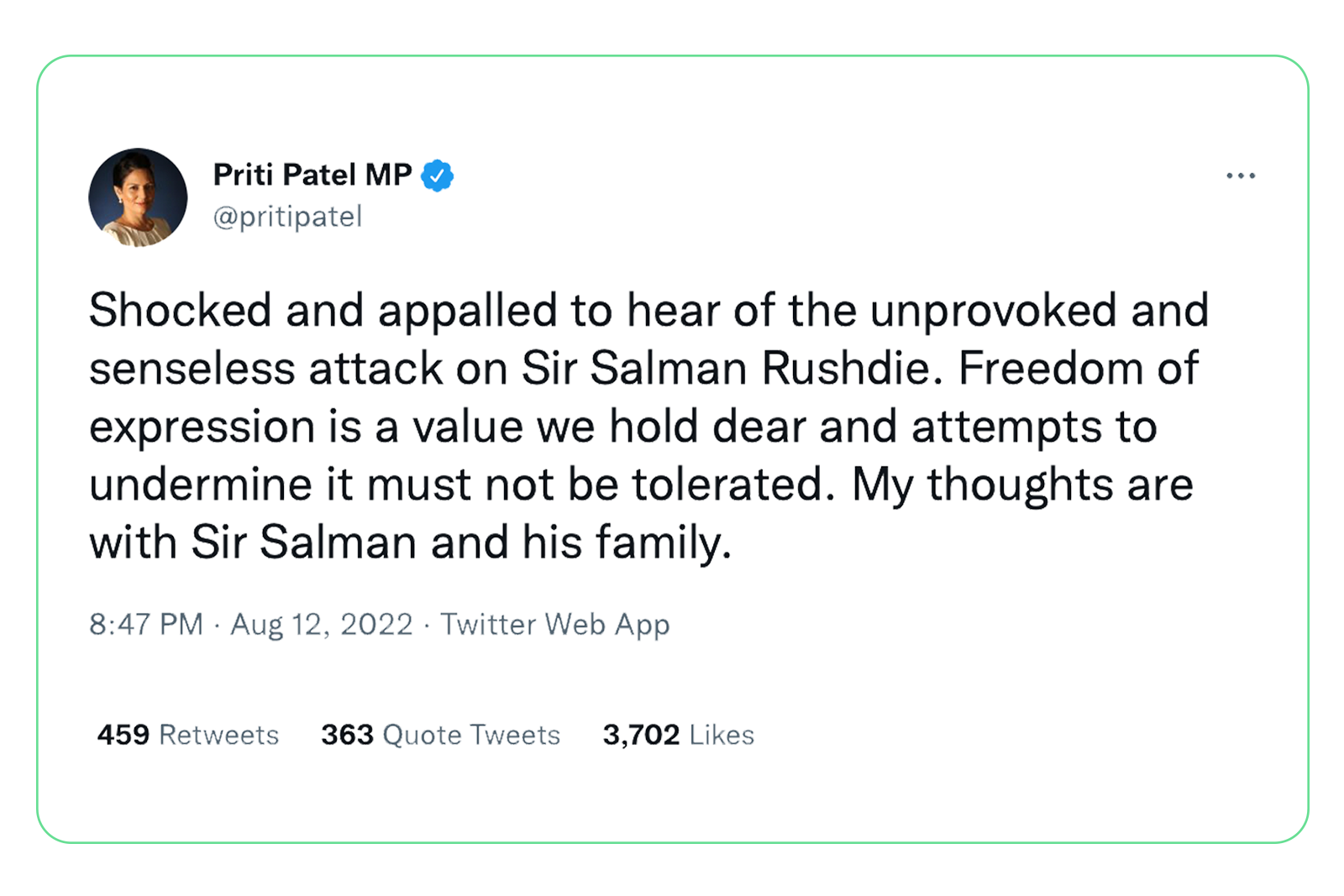

Former British Home Secretary Priti Patel tweeted that she was “shocked and appalled” by the attack on Salman Rushdie last month. She wasn’t as shocked and appalled and holding dear the value of freedom of expression back in June, when she approved the US government’s baseless request Julian Assange’s baseless extradition request to the US.

The truth is, accountability intolerance is inherent to power — be it democratic or authoritarian. Dissent isn’t only unwelcome, it’s oftentimes life-threatening. Those whose malfeasance and abuse of public position have been exposed, readily crack down on anyone who dares to do it, no matter their intent. In cases like this, saving face is crucial. The embarrassment caused by such revelations, usually results in a combination of two tactics: 1) divert the attention from the behaviour that has been exposed — by demonising those who have brought that behaviour to light, and 2) use whatever means necessary, however immoral or illegal, to punish them, thus demonstrating to others what will beset them if they ever think to follow the example.

In 2019, former Australian PM Scott Morrison said that Julian Assange “should face the music” in his fight against extradition to the United States on espionage charges. Throughout Assange’s 12-year fight with the establishment, this sentiment has been adopted by other high-profile politicians, public figures, ordinary citizens, even journalists, all of them either consumed by mania for careerism and financial gain, or completely wilfully oblivious to the facts of this vindictive persecution.

Calling Assange a traitor when he’s not even an American citizen while openly urging for his assassination should be worrisome (to say the least) even for Assange’s most vehement detractors. As Mary Dejevsky recently argued, Assange is a complex figure who does claim strong emotions for and against. However, whether we personally sympathise with him or disagree with his actions, there’s no excuse for turning a blind eye to the pyramid of judicial, moral, and physical abuse perpetrated against him since 2010.

Of course, this story should never have been about Assange. Although his character has a bearing on his political views and professional activities, the focus should have been on what WikiLeaks revealed. Our political system is so depraved, though, that despite the fact the war crimes and corruption WikiLeaks exposed have never been denied or disputed, those who blew the whistle are the ones who find themselves imprisoned or exiled, while no member of any government, military or intelligence service has ever been held accountable. All we’ve heard is false narratives about threatened lives and compromised national security. Twelve years later, no such harm has surfaced.

WikiLeaks was founded in 2006 but it wasn’t until 2010 that they came to public prominence. The reason was the massive leaks theypublished about war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. Photo credit: Flickr

In a 2011 debate about the social value of whistleblowing, British journalist and author Douglas Murray argued that “democracies and democratic governments can be and in most cases are at some point dishonest and yes, they can be corrupt” in his attempt to defend the view that whistleblowers rather endanger than save lives. He went on to say that democracy is a “deeply flawed system”, but it is by far the best thing we have going.

Murray is not alone in holding that worldview but a defence like this sounds to me as if it’s somehow wrong and bad to try and make our flawed democracies less flawed — by bringing their flaws to the fore of public debate and collectively trying to better our political reality. Murray spoke about checks and balances and voting rights as more honourable alternatives to whistleblowing. Although these checks and balances do in theory give the public some form of power in democratic societies, they are themselves not immune to corruption — many people who are in the higher echelons of government happily enable criminal and unethical behaviour — to them, lying and covering up abuses of authority is always preferable to admission of guilt, be it because they want to progress their own careers or because they genuinely believe in the pernicious doctrine that the aims justify the means.

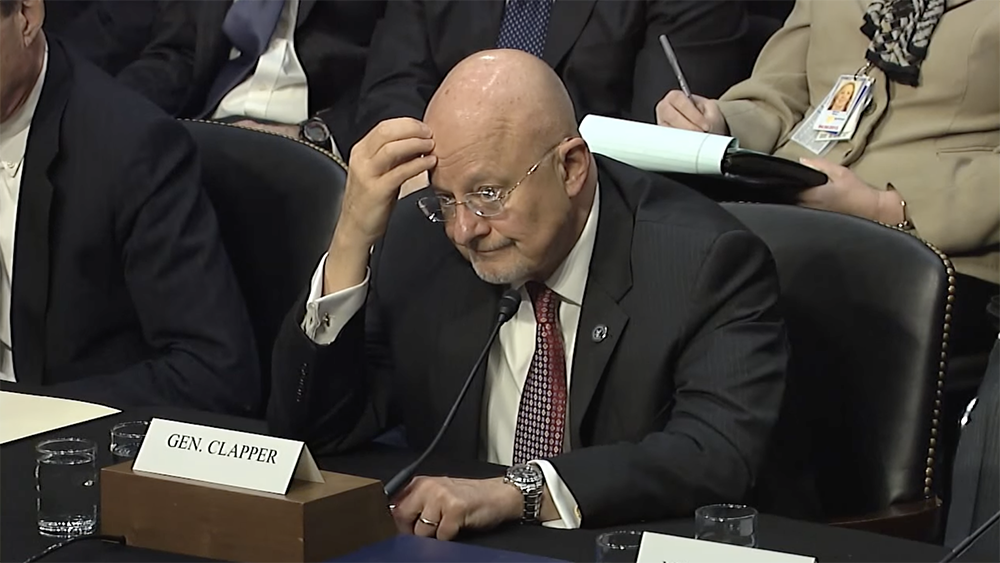

While testifying before Congress in 2013, former NSA Director James Clapper said that the NSA was “not wittingly” collecting any type of data on the American population. Few months later, the Snowden revelations showed this wasn’t the case. In 2019, Clapper clumsily tried to justify his answer by saying he misunderstood the question at the time.

In his book Permanent Record, Edward Snowden, explained his reluctance to use “the proper channels”, writing:

"

In my case, going up “the chain of command,” which the IC prefers to call “the proper channels,” wasn’t an option as it was for the ten men who crewed on the Warren. My superiors were not only aware of what the agency was doing, they were actively directing it — they were complicit.

In organizations like the NSA — in which malfeasance has become so structural as to be a matter not of any particular initiative, but of an ideology — proper channels can only become a trap, to catch the heretics and disfavorables. I’d already experienced the failure of command back in Warrenton, and then again in Geneva, where in the regular course of my duties I had discovered a security vulnerability in a critical program. I’d reported the vulnerability, and when nothing was done about it I reported that, too.

My supervisors weren’t happy that I’d done so, because their supervisors weren’t happy, either. The chain of command is truly a chain that binds, and the lower links can only be lifted by the higher.” (Snowden, 2019, p.235)

This is not an isolated case. Few years before Snowden decided to report the US government’s illegal surveillance programme to the press, Thomas Drake also tried to use the chain of command to address mismanagement inside the NSA, only to get himself expelled from the agency and indicted on espionage charges.

Anyone who supports whistleblowers can’t seriously believe that government secrecy is an inherently bad thing, but the whistleblower critics seem to confuse legitimate secrets as in operational strategy, with blatant wrongdoings and criminal activity. I agree with Douglas Murray that a discussion around who guards the guardians of truth and who decides what the public should know, is pertinent, but he hasn’t made a case for why governments are better suited to be these guardians than the public.

As was pointed out in the whistleblower debate, a good practice in this direction is to team up with other media outlets and organisations to vet, curate, verify and redact the information which will be disclosed so that individuals who might be put in harm’s way through the revelations, are protected. This is what whistleblowers actually do, that’s why they go to the press instead of dumping the information somewhere on the internet or even offline and be done with it. This is also what Wikileaks did, although their publishing partners at the time – The Guardian, The New York Times, Der Spiegel, are enjoying their freedom while Julian Assange is rotting in a prison cell for doing exactly what they did and what any real journalist would do.

In the absence of knowledge, the flawed democracy position, although disingenuous, would have been somewhat understandable. It would have made some sense in the pre-Bush era, before the disclosures around Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, before John Kiriakou spoke out about the US government torture programme (their preferred term is enhanced interrogation), before Chelsea Manning shared the Collateral Murder video with WikiLeaks, before Edward Snowden told us about the NSA surveillance programme, before Daniel Hale unveiled the Obama administration extrajudicial drone killings.

Some people have obviously accepted Obama’s “we tortured some folks” admission as an apology and a promise the US government will never commit such crimes ever again although I’m sure it was not intended as such. But to maintain the flawed democracy position after what’s been made known and we continue to witness, is not only ignorant, it’s borderline criminal.

I also think it’s untenable to claim that whistleblowers, by revealing government secrets, are betraying their country and breaking the law so they deserve retaliation —moral decency should be above any man-made laws, and although morality should be reflected in our legal systems, it not always is — sometimes what’s deemed absolutely lawful is deeply morally perverted.

12 years of obfuscation, dehumanisation and denied justice

In the lead-up to Assange’s formal arrest and incarceration in a maximum-security prison in London in April 2019, the interested political parties, with the kind help of their media partners, managed to create the convincing image of the “rapist on the run”, the “paranoid narcissist” and the “hacker” anarchist who deserves what’s coming for him.

For those concerned with Assange’s history of sexual proclivity and his supposed vendetta against the US government, Nils Melzer’s The trial of Julian Assange will be a seminal read. Melzer is UN’s former Special Rapporteur on Torture, former legal advisor to the International Committee of the Red Cross, Professor of International Law at the University of Glasgow, and someone who, at first, thanks to the public vilification of Assange, didn’t hold sympathetic views towards him.

Since early 2019, he has been trying, in his own words, to sound the fire alarm to the grave injustices and inhumane treatment perpetrated against Assange for more than a decade, only to be stonewalled by the governments of Sweden, the United States, and the United Kingdom, which, as he put it, have demonstrated a “royal condescension” towards his mandate.

Anna Ardin, one of the appropriated plaintiffs in the sex allegations case from 2010, found (around 44:50) Melzer’s book to be “confused, having built the case on bits of evidence”. Melzer is very methodical, impartial, and consistent in his investigation and the analysis of the accompanying circumstances around the case, so “confused” is a weird way to characterise his book.

Such reaction is also strange, having in mind that Melzer described both Assange, and the two women as “equally credible”, “victimized” and “instrumentalized for the purposes of a political persecution” (Melzer, 2022, p. 104) — a position he maintains throughout the book, condemning not only the gross judicial misconduct against Assange but also the women, including the public blowback and smears against them as honeytraps and CIA agents. I’d imagine a person who is seeking justice they claim they never received, to agree with an investigator who concluded they’ve fallen victim to the Swedish judicial process, especially when the emails, messages, witness statements and documentation he reviewed, although redacted, were explicit and consistent with his conclusions from the actual judicial proceedings.

Here's how Melzer himself writes about the Swedish and British authorities’ casual disregard for his mandate and their refusal to collaborate and provide documents, statements, and evidence in their unredacted, original form.

"

Even in mature democracies, such as Sweden, the United Kingdom, Germany and the United States, this widespread, clearly abusive practice is employed to prevent the transparency and oversight pursued by applicable freedom of information legislation, thus effectively suppressing the public’s right to know the truth about the exercise of governmental power.

This means that in investigating the case of Julian Assange I found myself confronted with countless pieces of a puzzle, some of which I had received in multiple copies while others are still missing. Even now, therefore, I have no way of knowing with certainty how many pieces the whole puzzle actually comprises. The reason for this continued uncertainty is that the involved states not only refuse to “fully cooperate” with my mandate as required by the relevant UN resolutions, but also openly violate their international obligations under the Convention against Torture and other applicable human rights treaties.

States are not only called to respond to all queries transmitted by a UN special rapporteur, but they are also legally obliged to conduct a prompt and impartial investigation whenever they have reasonable grounds to believe that torture or ill-treatment have occurred within their jurisdiction, to prosecute violations, and to provide redress and rehabilitation for the resulting harm. With their blatant sabotage of my investigation, these states deliberately undermine the purpose of my UN mandate and, at the same time demonstrate the lack of credibility of their own human rights policies” (Melzer, The trial of Julian Assange, p. 107-108).

In August, Australian authorities banned the distribution of Melzer’s book to local MPs and the media, when Assange’s brother and father tried to persuade the Australian government to finally intervene and defend their fellow citizen as they almost pledged to do before they commenced into office.

Make of these facts what you will, but even if we disregard Melzer’s investigation, it’s clear that those who reported on Assange’s case throughout the years, have done a very lousy job and demonstrated absolute disregard for the responsibility that comes with the profession they claim to be practicing. Given the political dimension of the case, the severity of the allegations and the strong reactions to Assange’s character, an effort for objectivity was the least they could do. After all, the average citizen usually doesn’t have the time and probably motivation to do their own research in convoluted cases like this, they would instead take the media reporting at face value.

Some of the “legal myths” which have circulated the media throughout the years, bear mentioning here. It is often claimed that Assange sought asylum in Ecuador’s embassy in London to avoid facing the sex allegations in Sweden rather than to avoid extradition to the US from Sweden, and his fears were unfounded because there was no extradition request raised by the US at the time (it was revealed in 2018 that there was a sealed indictment against Assange and he has been on the US authorities’ radar since WikiLeaks published troves of war logs and diplomatic cables in 2010).

Assange requested to receive written assurances from Sweden that, should he travel to the country to face the sex allegations, Sweden would not surrender him to the US. That request has been ridiculed as a demand for special treatment and a condition “impossible” for any country to satisfy because states cannot provide assurances before an actual extradition request has been submitted. As Nils Melzer points out in his book, and as can be inferred from the UNHCR Note on Diplomatic Assurances and International Refugee Protection:

"

...’diplomatic assurances’ are a standard instrument of international relations and are widely used around the world, especially in connection with the extradition and deportation of foreigners. The extraditing or deporting state requests written assurances from the destination or transit state that the person to be extradited will not be executed, tortured or otherwise mistreated under any circumstances, that their procedural rights are guaranteed and that - in accordance with the universal principle of nonrefoulment - they will not be extradited to a third state in which their human rights protection is not guaranteed.

In practice, such non-refoulment guarantees are routinely given, naturally without requiring a prior extradition request by the potentially unsafe third state. Likewise, the all-time favourite smokescreen advanced by Western democracies trying to evade their human rights obligations, namely that the government cannot “interfere” with pending judicial proceedings, does not stand up to scrutiny. In Sweden, as in most other countries, the government has the prerogative to refuse any extradition on political grounds, irrespective of whether it has been approved by the judiciary. Clearly, the reasons why Sweden consistently declined to offer Assange a guarantee of non-refoulment were not constitutional, but purely political, and Assange had every reason to be concerned, particularly given the longstanding . and unconstitutional . collusion between Stockholm and Washington in matters of national security and intelligence, which WikiLeaks itself has exposed to the world” (Melzer, The trial of Julian Assange, p.166- 167).

It should be noted, however, that diplomatic assurances alone are not legally binding for the receiving state, and, as Amnesty International maintain, they are inherently unreliable because the risk of torture is implicit in the necessity to obtain such assurances. Additionally, there is no clear procedure and mechanism to ensure the receiving state is abiding by the provided assurances, the legal language they use is ambiguous and giving leeway to work around them, and there have been many examples where the receiving state has violated assurances they’ve given prior to somebody’s extradition or deportation.

Back in 2010, however, Assange’s main concern wasn’t the unreliability of diplomatic assurances, he was cooperative with the Swedish authorities and willing to face the charges, if only the Swedish prosecution demonstrated more interest in uncovering the truth and more willingness to resolve the case by ensuring Assange that they would not deport him to the US.

Apparently, they couldn’t make that commitment because their decisions were being taken in Washington.

Another legal myth disseminated by the media, was Assange’s “unreasonable fear” that extradition from Sweden was more likely than from the UK. It was claimed that extradition from Sweden to the United States will be “more difficult” because “it would require the consent of both Sweden and the United Kingdom”. While that is correct — Sweden would have to obtain UK’s approval to extradite Assange, the assumption that if they wanted to, the US government would pressure Sweden more easily than the UK, doesn’t sound that crazy. What’s more, neither Sweden, nor the UK have ever expressed any sympathies with Assange — hypothetically, they would have been equally happy to hand him over to the US.

Green was right then as he would be now — “complainants of rape and sexual abuse have rights too” and provided Assange’s guilt in these allegations is proven, he should absolutely be held to account. But neither then, nor now has such guilt been proven beyond reasonable doubt, while Assange has been treated by the media and the authorities of Sweden, Britain, and the United States as a convicted rapist with a long history of criminal transgressions since the early hours of the preliminary investigation, and no due process or presumption of innocence has been upheld.

Not to mention that, on a closer look, the due process violations of the Swedish prosecution would have been obvious even back in 2010, should someone have bothered to look further than the headline.

Green brushed off the fact that, upon filing the complaint in 2010, the Swedish prosecutors dropped and reopened the case in the course of just a few days and then waited for a whole month before they requested to interrogate Assange, even though he proactively urged them to do so, as a procedural question for the Swedish courts to challenge. The police issued an arrest warrant on the same day the two women visited the police station — 20th August 2010. Assange was still in Sweden and he wasn’t hiding, why wasn’t he arrested?

Instead, he learned about the allegations from the press (allegedly leaked to them by the prosecution itself!), he did postpone his departure from Sweden by a month and was willing to be questioned on several occasions before the Prosecution Authority (mis)led him to believe he was free to leave the country. When he finally did leave, Sweden issued a European Arrest Warrant and made it look like he fled the country to evade justice, knowing he had been sought for questioning.

At that time, unlike Green’s claims, Assange was wanted for interrogation, not arrest. As evidenced by Nils Melzer’s investigation, the prosecution had just reopened the case and amended the allegations. They conducted secondary interviews with the alleged victims and by protocol, should have interviewed the suspect, as well. They had an SMS exchange with

Assange’s Swedish lawyer to arrange an interview, but he couldn’t get hold of his client. It’s true that later, the lawyer made it look as if the prosecution never bothered to establish contact to schedule an interview, but it’s also true that the latest information Assange had at the time was that he wasn’t wanted for questioning and was free to leave the country.

In the next two years, Sweden would continuously try to extradite Assange from Britain to face the sex allegations on Swedish soil, he was arrested, released on bail, and placed under house arrest until his legal options to fight extradition were exhausted, and he sought political asylum from Ecuador, becoming a permanent resident of the Ecuadorian embassy in London in August 2012.

For seven years, Assange has been unable to leave the confines of the Ecuadorian embassy in London, vociferously guarded by the British Metropolitan Police at all times. In an interview with Democracy Now, Nils Melzer answered the former British Foreign Minister Jeremy Hunt’s remarks that Assange has always been “free to leave” the embassy saying: “With all due respect, Sir, Mr. Assange was as free to leave as someone who is sitting on a rubber boat in a shark pool”. Photo credit: Flickr

The charade of justice continues

As Melzer observed in his book, over nine years, the Swedish courts have resorted to performing all kinds of “judicial acrobatics” to keep the Swedish case alive, dropping and reopening it on several occasions, without ever having any substantive evidence to arrest or indict Assange. The case, of course, was the necessary smokescreen to keep Assange in a legal limbo until the US government could find a way to officially persecute him. In 2017, the Swedish prosecutor discontinued the investigation only to suddenly reopen it in April 2019 just days after Assange was dragged out of the embassy by the British police and put in a highsecurity prison for skipping bail (!) where he still remains on remand without a conviction.

The sex allegations case was finally closed in November 2019 due to lapsed statute of limitations (it had also served its political purpose). The abuses of due process in the Swedish investigation described above are by no means an exhaustive list but they have been followed by just as egregious human rights violations during Assange’s supposed self-imposed isolation in Ecuador’s embassy in London, and the ongoing show trial designed to finally extradite him to the United States and lock him up for the preposterous sentence of 175 years.

The mere fact that Assange is indicted for publishing truthful information, whose authenticity has never been challenged — essentially for practicing investigative journalism, is mind-boggling even for a flawed democracy, and, as the national security reporter James Risen argued, should be deeply concerning for all journalists and citizens.

That is the free press defence argument which has been taken up even by previously critical of or indifferent to Assange news outlets, also expressed by human rights and press freedom organisations like Reporters without Borders, Amnesty International, Freedom of the Press Foundation, ACLU, politicians, artists, doctors, academics, and lawyers around the world. As Risen remarked, what Assange has been imprisoned for and what WikiLeaks is doing, isn’t any different from what major media outlets like The New York Times and The Guardian are doing:

"

If the government can charge Assange for conspiring to obtain leaked documents, what would stop it from charging the CIA beat reporter at the New York Times for committing the same crime?"

Glenn Greenwald rightly pointed out that the impossibility to discern WikiLeaks’ activity from any “traditional” media agency’s (protected under the First Amendment), was namely the reason why Obama’s administration decided not to prosecute Assange. Unfortunately, this hasn’t prevented ludicrous insinuations against him that he’s not a “real journalist” (and if that were a legitimate argument, this somehow makes his arbitrary imprisonment just), that he overstepped regular journalistic activity, that he helped Trump win the 2016 election because he hates Hillary Clinton.

What was unconstitutional under Obama, quickly became a reality under Trump’s CIA Director Mike Pompeo who declared WikiLeaks a “non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors like Russia” in 2017 to ready the ground for the stitched up prosecution against him. We didn’t have to wait long to witness the bipartisan “respect” for civic liberties when the democratic saviour Joe Biden ascended to the White House in 2020 — his DOJ has been demonstrating the same eagerness to strangle press freedom for good, regardless of Constitution, rule of law, morality, or human decency.

As Greenwald put it back in 2018:

"

…the grand irony is that many Democrats will side with the Trump DOJ over the Obama DOJ. Their emotional, personal contempt for Assange . due to their belief that he helped defeat Hillary Clinton: the gravest crime . easily outweighs any concerns about the threats posed to press freedoms by the Trump administration’s attempts to criminalize the publication of documents”.

The blatantly partial treatment of Assange in the British courts was demonstrated from the very first hearing — the judge called him “a narcissist who cannot get beyond his selfish interests”.

Later, Judge Emma Arbuthnot refused to recuse herself from the case due to an obvious conflict of interest as her husband was a sitting member of the House of Lords and has been involved with the British intelligence services who have suffered reputational damage as a result of WikiLeaks’ disclosures.

Last year, it was revealed that the US government’s primary witness in the indictment against Assange, was in fact recruited by the US authorities to fabricate the accusations. Shortly after that, Yahoo News published a summary of a CIA plot to kidnap and possibly assassinate Assange while he was still at the Ecuadorian embassy, according to the testimony of former CIA officials.

Confronted about this leak of information, former CIA Director Mike Pompeo gave an evasive, Bill Clinton-like but very telling answer: “Makes for a pretty good fiction… I can’t say much about this, other than whoever those 30 people who allegedly spoke with one of these reporters, they should all be prosecuted for speaking about classified activity inside the Central Intelligence Agency…We never conducted planning to violate US law, not once in my time”.

On top of that, as Kevin Gosztola and other independent journalists reported, Assange has continuously been denied proper access to his lawyers during and around the hearings, and in the height of the Covid pandemic, the judge denied him bail despite his suffering from a chronic lung disease, although he is not serving a sentence and he isn’t violent or posing any threat to society. In October 2021 he suffered a minor stroke and attention to his progressively deteriorating health has been raised on numerous occasions by doctors, psychiatrists, his family, and human rights advocates.

During his hearings in the British courts, Assange has been denied the ability to sit with his lawyers. Instead, he has been caged in a glass boxat the back of the room. One would imagine he is a violent criminal, tried for crimes against humanity. As The Grayzone’s Max Blumenthal wrote, Assange is being held in more restrictive conditions than Nazi collaborators. Photo credit: The Grayzone.

Towards the end of Assange’s asylum at the Ecuadorian embassy in London, the government in Quito was replaced with much more US-friendly members. This enabled the CIA to gain unobstructed access to Assange through the security firm UC Global which spied on him on a daily basis and violated his right to privacy and confidential communication with his visitors, lawyers and doctors. This led some of them to file a lawsuit against the CIA for unlawful spying and seizure of their private data during their visits to the embassy. We are yet to see how this lawsuit will conclude.

In April 2019, Ecuador, pressured by the UK authorities, revoked Assange’s asylum and canceled the Ecuadorian citizenship it had given him a year earlier, without any notice. Instead, they welcomed the British police in the embassy to expel Assange by force, violating all international conventions on protection of asylees.

In a country that respects the rule of law and quite frankly — basic human decency, each of these facts alone would have been more than enough grounds for this concocted trial to be dropped and Assange released. If Assange’s case is anything to go by, neither Britain, nor the United States, nor Sweden or Australia can claim that title.

In June this year, former British Home Secretary Priti Patel “upheld” her beliefs in democracy and freedom of the press by greenlighting Assange’s extradition to the US, which Judge Baraitser blocked in January due to Assange’s fragile mental state and risk of committing suicide.

When the extradition was first denied, the US was quick to provide assurances that, if extradited, Assange 1) would not be placed under special administrative measures unless he committed any “future act that met the test for the imposition of a SAM” and 2) “if Mr Assange is convicted in the United States he will be eligible, following conviction, sentencing and the conclusion of any appeals, to apply for a prisoner transfer to Australia to serve his U.S. sentence”.

Any reasonable person would immediately reject the validity of these assurances solely because of the vague language they are written in, let alone the US’ historical hostility towards Assange and their negligence for his legal and human rights. Clearly, the United States reserves the right to impose SAMs at their discretion which sounds more like a promise than an eventuality.

Furthermore, as stated in the US appeal, Assange will be able to serve a sentence in Australia “as Australia provides its consent to transfer under the COE Convention” which rests on a hypothesis at best because the Australian government at no point has expressed any meaningful interest in the fate of their fellow citizen.

If we, for the sake of argument, disregard the language used here (which we shouldn’t), these assurances would still be highly questionable. As noted previously, diplomatic assurances are not legally binding for the state that provides them, there’s no mechanism to ensure the issuing state abides by them, and the US in particular, has a track record of violating diplomaticassurances for other detainees, which in a political case like Assange’s, renders them absolutely laughable.

Currently, Assange’s lawyers are appealing the extradition approval before the UK High Court, other avenues for appeal are the UN Human Rights Office and the European Court of Human Rights. Judging from how the trial has unfolded so far, the prospects are grim but, on the flipside, Assange receives immense support from independent journalists and media outlets, human rights organisations, ordinary citizens, politicians, and other public figures, who are advocating for his release in various ways. That support is critical because it puts pressure on the governments and judiciary, and limits their attempts to hide Assange from the public eye so that they can continue to violate his rights as they please.

Just recently, Mexico’s president López Obrador awarded Assange keys to Mexico City and has offered to grant him asylum. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the left coalition NUPES in France has also expressed sympathetic views towards Assange. Australian Independent MP Andrew Wilkie has long been an advocate for Assange. So have the British Labour Party’s former (ousted) leader Jeremy Corbin and Greece’s former finance minister and current MP Yanis Varoufakis.

Eric Levy, a staunch supporter of Assange and a famous anti-war campaigner. He passed away at 93 in July this year but is still an inspiration to many people around the world. Photo credit: Flickr

Roger Waters has been an ardent supporter of Assange. He is currently on his “This is not a drill” tour, which is a form of anti-war, antiestablishment initiative. He partnered with Assange Defense campaign to set up a Free Assange table at every show to draw attention to Assange’s case. Photo credit: Flickr

In 2015, Davide Dormino (pictured), an Italian sculptor and artist, revealed the Anything to say? project — a body-size sculpture of Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, and Chelsea Manning, which he created as a sign of support for them and protest towards the injustices they’ve endured. The sculpture’s first appearance was in Berlin but since then, it has toured other cities across Europe to raise awareness to the issues of free speech, unchecked power, and human rights. Photo credit: Flickr

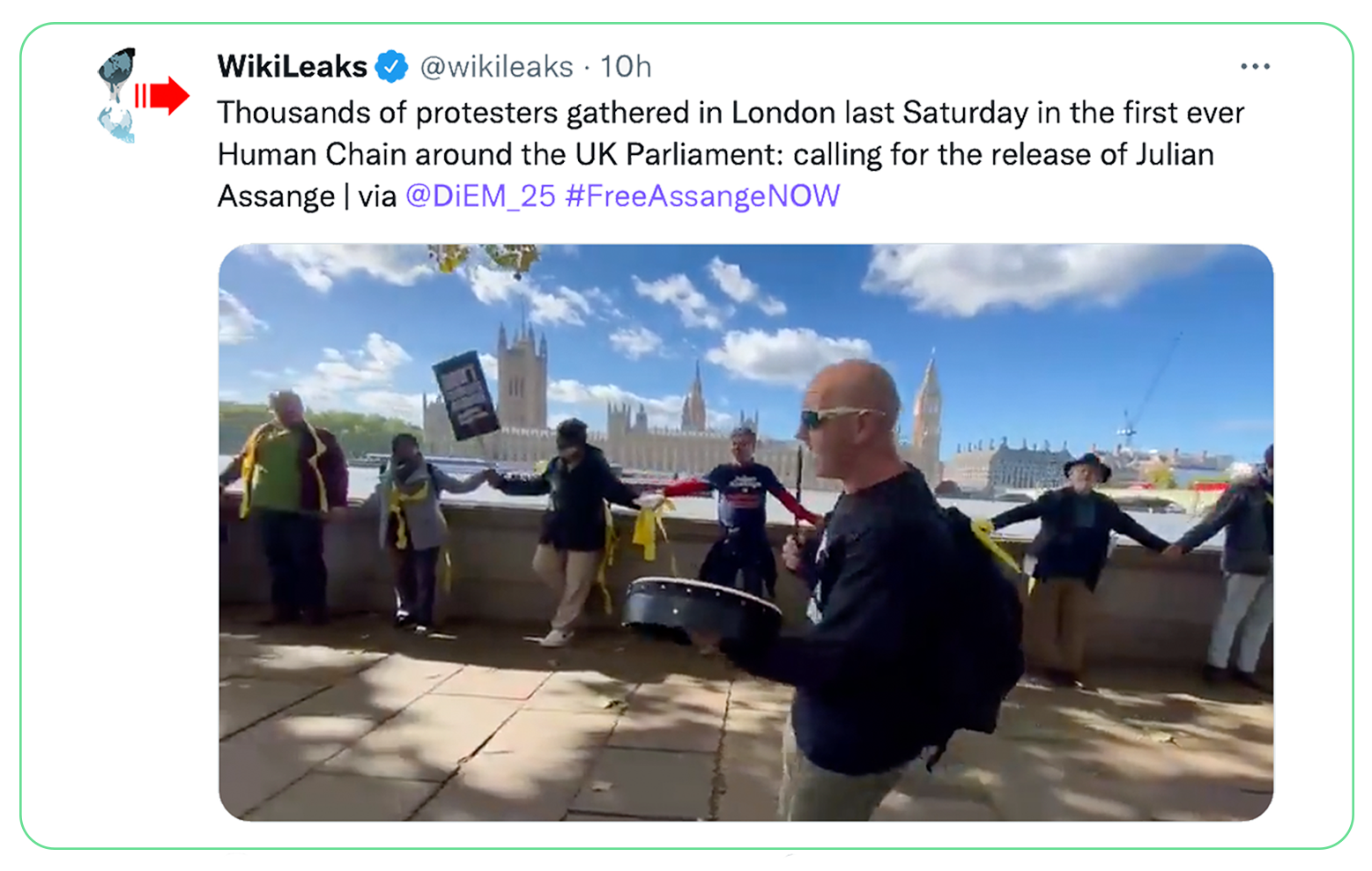

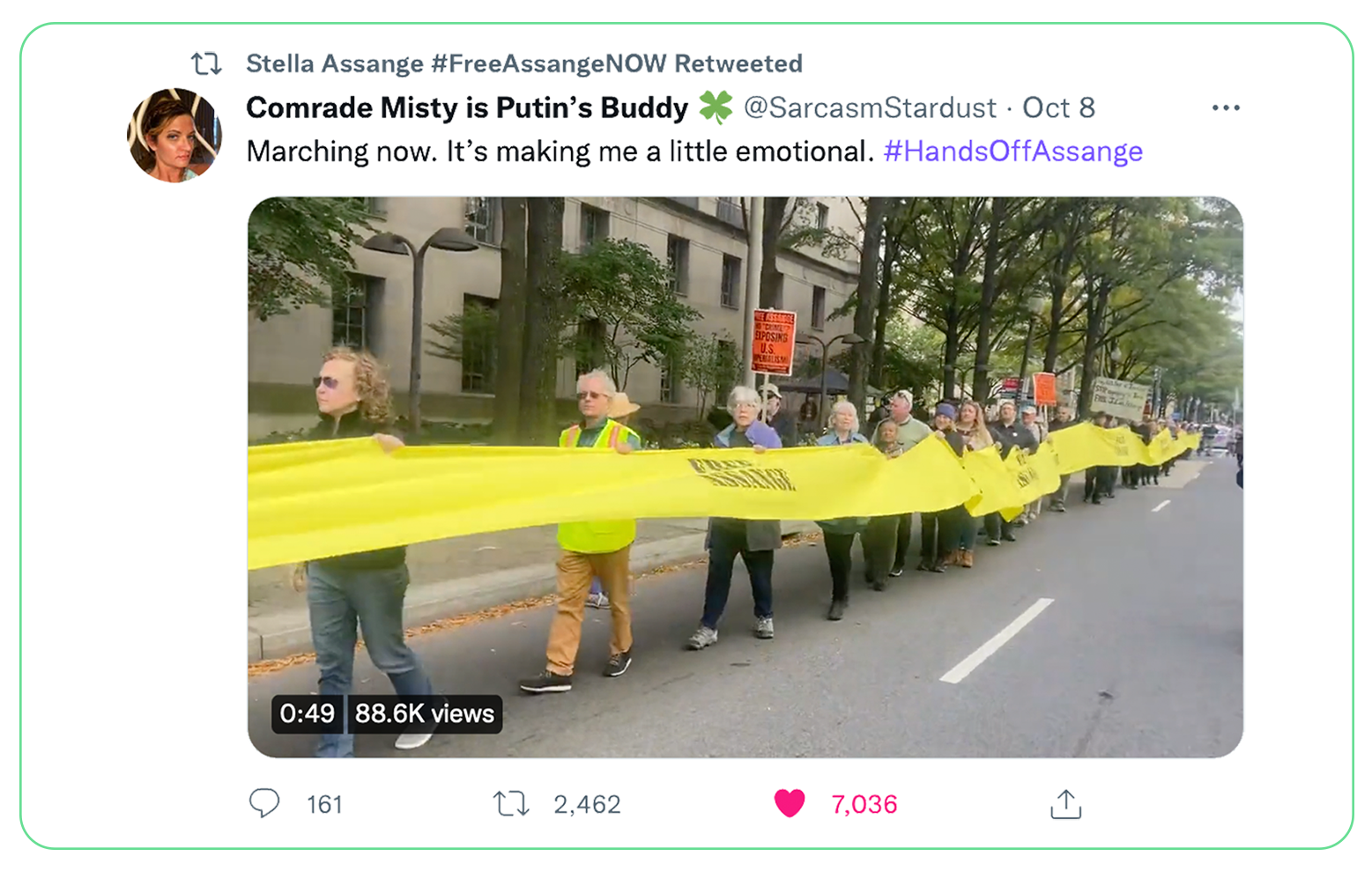

Last Saturday, on 8th October, thousands of Assange supporters gathered in several cities around the world to demand his immediate release. The legacy media, in their almost nonexistent reporting of this international show of solidarity, claimed that “hundreds of protesters” gathered in London, whereas the real number was closer to several thousand people. Protesters and supporters of a free press formed a human chain around the Houses of Parliament to show their solidarity for Assange and disapproval of his arbitrary detention and the despicable attempts of the US to extradite him for practicing journalism.

People came from different parts of the UK but also other countries — Germany, France, the Netherlands, the US, Latin America, Africa, Bulgaria.

People were drumbeating, singing, wearing orange prison-like jumpsuits and the famous yellow ribbons which are a sign of solidarity with those who are far from home and hope they would return safely soon

Lambeth bridge in London was filled with Assange supporters. So were the opposite bank of the Thames, the Victoria Tower Gardens all the way to Big Ben and Westminster Abbey.

On 1 July, Kolja (right) started his long walk for Assange from his hometown of Hamburg in Germany to London in an attempt to raise awareness to Assange’s case and demonstrate his support. He went to Belmarsh prison and was also at the Surround Parliament rally on 8 Oct.

Prominent figures like Russel Brand, Jeremy Corbyn and Craig Murray made an appearance and spoke at the rally in London. Current editor-in-chief of Wikileaks Kristinn Hrafnsson and one of Assange’s lawyers Jennifer Robinson were also there to support Stella Assange and her family.

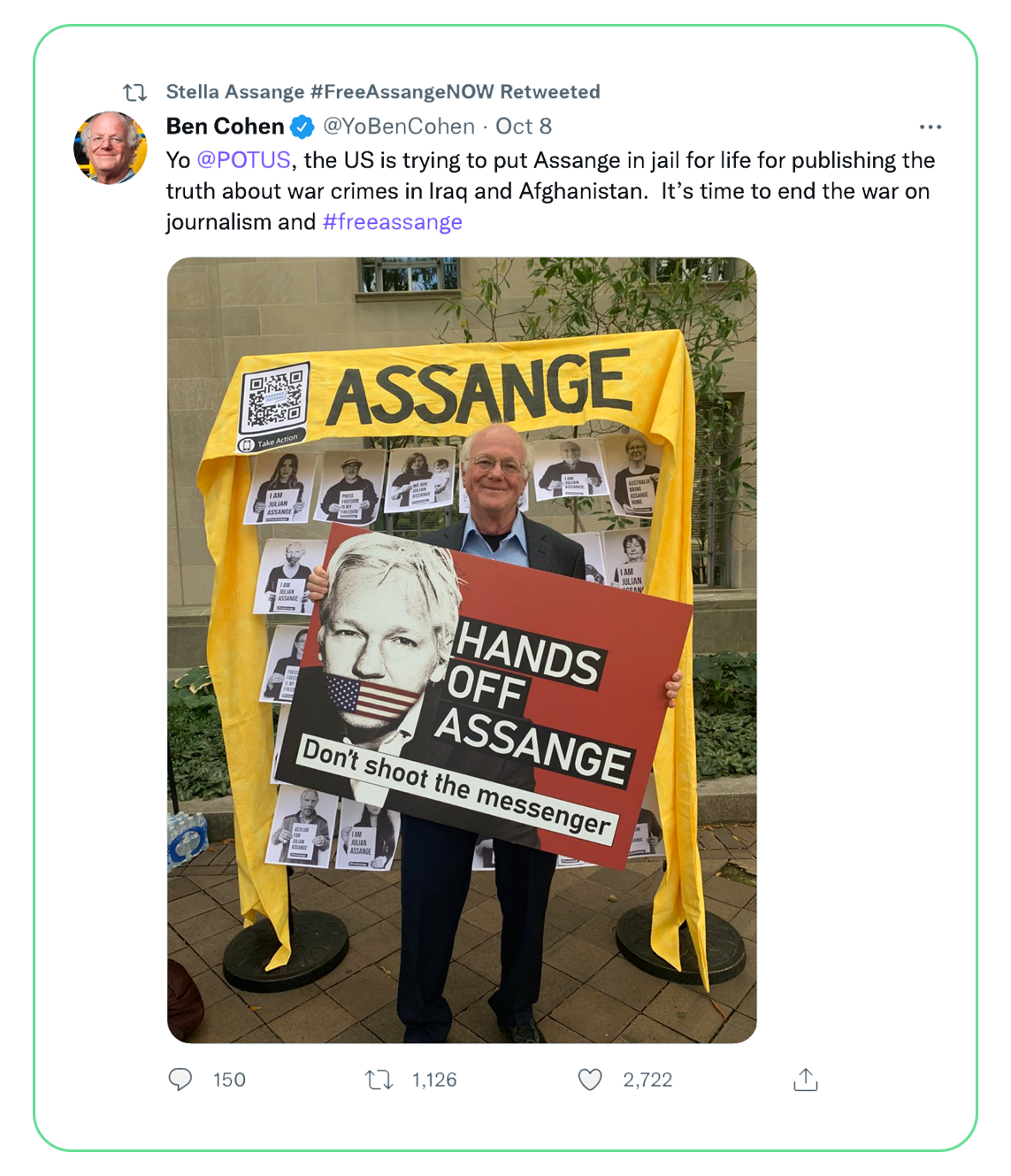

Similar initiatives took place in other countries, too — the US, Australia, Croatia, Brazil, even Bulgaria which isn’t usually a place of strong activism. At the “Hands Off Assange” rally in front of the Department of Justice in Washington DC, former UN Weapons Inspector and former US Marine Corps Intelligence Officer Scott Ritter gave an ardent speech, in which he talked about the oath he and others like him had taken, as an oath not to defend “the President of the United States no matter what”, but rather to defend the Constitution of their country whose First Amendment is freedom of speech. This reminded me of the absurd belief of people who criticise Assange and whistleblowers more broadly because they’ve supposedly “betrayed their country”. If any argument about betrayal can be made in such circumstances, it’s a betrayal of a rogue state, not of one’s country but that conflation of state with country is intentionally designed and spread around by the perpetrators of state-sanctioned crimes because the elusive veil of secrecy and national security rhetoric is the only place they can hide behind.

Assange supporters marched around the DOJ in Washington and gathered in front of the building to hear renowned figures speak about the implications of Assange’s case for press freedom and democracy.

Chris Hedges who also spoke at the DOJ rally, concluded his speech by saying:

"

We are here to fight for Julian. But we are also here to fight against powerful subterranean forces that, in demanding Julian’s extradition and life imprisonment, have declared war on journalism. We are here to fight for Julian. But we are also here to fight for the restoration of the rule of law and democracy. We are here to fight for Julian. But we are also here to dismantle the wholesale Stasi-like state surveillance erected across the West.

We are here to fight for Julian. But we are also here to overthrow — and let me repeat that word for the benefit of those in the FBI and Homeland Security who have come here to monitor us — overthrow the corporate state and create a government of the people, by the people and for the people, that will cherish, rather than persecute, the best among us".

Another speaker, Esther Iverem, an artist and writer, said:

"

I want the Clintons, the Obamas, the Bushes, and Mike Pompeo to know that you may try to silence Julian Assange but the thing about facts, is that facts don’t die, they don’t die. They don’t change, they don’t become unfacts, they don’t become untrue. Facts never become false, so even in the current psyop about Ukraine, you may try to sell lies, you may try to erase the history of Stepan Bandera, you may try to take Victoria Nuland’s video off of YouTube…and you may try to erase the history of garment workers in Haiti, who were denied a minimum wage under Hilary Clinton when she was over at the State Department but the thing is that the fact that that happened, doesn’t die…

Wikileaks was and is an antidote for this kind of this imperialist psychosis, that things that we will forget that the millions of people killed in Vietnam or all these wars, that the people who have been tortured, that the people who have been starved like they’re being starved right now in Afghanistan because we’ve stolen their money.

They think that all of these things will disappear, and I think it’s a type of psychosis, and Wikileaks was and is an antidote for this”…This whole group of cannibal imperialists, they aren’t afraid and angry because Wikileaks makes them look bad, they are afraid and angry because Wikileaks gives us information to fight back”.

Guest speakers at the DOJ rally included Ben&Jerry’s founder Ben Cohen (pictured), independent journalists Kevin Gosztola, Dan Cohen, and Chris Hedges, Consortium News Editor Joe Lauria, comedian Randy Credico, CIA whistleblower John Kiriakou, and others.

Last week, Assange was nominated and became one of three finalists for the European Parliament's Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought along with “The brave people of Ukraine, represented by their president, elected leaders, and civil society” and The Truth Commission in Colombia. The ongoing official EU narrative might prevent Assange from winning this prize but that’s not the point. Assange is awarded numerous prestigious journalism prizes and his contributions to investigative journalism continue to be recognized the world over. Earlier this year, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for the third time. If he finally wins, it will be a great irony to share that honour with proponents of the US endless war policy, like Barack Obama.

An independent documentary about Assange is currently in production and will hopefully be released next year. Unlike other documentaries about Wikileaks and Assange, its producer Kym Staton is focusing primarily on the importance of Assange’s work and the grave consequences for media freedom which stem from Assange’s prosecution. People who have received some form of justice through Wikileaks’ publications, like survivors of Guantanamo are also said to be featured in the film, as well as notable whistleblowers like Daniel Ellsberg.

We can only hope that this growing support for Assange and what he stands for, will continue to multiply, and will finally result in an end to this farcical reality we’re living in. It’s equally important for this support to never get tired or apathetic to the attempts of those in power to silence us and diminish our efforts to demand real justice for Assange but also to stand for our own civil rights.

What makes Assange's case so different from any other case of denied justice?

The 1917 Espionage Act has been used to prosecute many people before Assange. Most of them have served or are still serving sentences, and this isn’t likely to change any time soon because a public interest defence isn’t allowed under the Espionage Act. As Daniel Larsen argued, the Espionage Act has morphed from an instrument to prosecute spies and dissenters who provided enemies of the country with national defence information, into a much broader and elastic concept designed to go after anyone whom the government disagrees with, regardless of their occupation, motivation, legal standing or moral convictions.

Last year, Rep. Rashida Tlaib proposed an amendment to the Espionage Act that would allow whistleblowers to explain to a jury their motivation for leaking classified information, and force prosecutors to prove intent to harm the national security of the United States when prosecuting someone. Her proposal was of course, rejected. Assange isn’t the first person to suffer the consequences of a corrupt judicial system and abuse of political power, nor has he suffered those consequences for the longest period. Nonetheless, the malignant, decade-long and concerted effort to crush him in every sense imaginable, which Nils Melzer described as “slow motion murder”, is hard to match. It also speaks to the absolute failure of societies who pride themselves on protecting human rights and the rule of law, to act upon these principles.

As Melzer phrased it towards the end of his book:

"

The problem is not the good or bad character of those at the top, but that we have created and maintain a political and economic system that allows for unmitigated power, secrecy and impunity. With such a lopsided system, we will not be able to effectively respond to the enormous challenges we face as a global community…Only on the basis of a sober sense of self-awareness will we be able to take political responsibility, expose harmful power structures, make the necessary systemic adjustments, and hold decision-makers accountable” (Melzer, 2022, p.333).

Assange devised a system with the specific purpose of exposing governmental misconduct and abuse of power. In that sense, WikiLeaks is a truly effective watchdog on abuses of authority.

That is the primary reason why four seemingly democratic governments are ruthlessly bending all legal and moral laws to shut him up and lock him away for good. This persecution is also a case in point for setting a very frightening precedent — if Assange is successfully extradited, tried, and convicted in a US court for publishing classified but truthful material, that will indeed be the end of investigative journalism, and any country would be able to request the extradition of a foreign journalist or publisher whose work has embarrassed them and disclosed reputationally damaging information about their government.

The Washington Post rightly observed in their tagline that democracy dies in darkness. In the case of Assange, I’m afraid, truth, and by extension — democracy, are dying in broad daylight.

To quote Edward Snowden, I think everyone should ask themselves: would you rather not know? I’m sure a lot of people would. But those aren’t the people who make this world a more just place.

About me

I am an editorial designer based in Bulgaria. I love animals, especially cats, tattoos, and almost anything black and white. When I'm not designing, I read, write, drive, watch documentaries, listen to podcasts, and talk to people about random and not so random stuff.

My mission

I'm on a mission to help truly independent journalism get to people in a comprehensive and visually-appealing format, so that they can form their opinions freely and make decisions based on honest and truthful reporting.

What is editorial design?

Simply put, editorial design is the design of magazines, newspapers, books, and other media publications, be it print or digital. In other words, it's the visual representation of journalism and information intended for public use.

EMAIL | LINKEDIN | INSTAGRAM | TWITTER

© 2024 | dessutom